19th January

It was only 185 miles from Ahe to Makemo, but upwind for a day and night, dodging squalls and taking every lift we could find in the variable breeze.

We were happy to reel in a fat yellowfin tuna, who supplied us with a few tasty meals.

That night we saw ‘moonbows’ in the dark sky, full rainbows between the clouds, with distinct bands of colour in the moonlight. Never seen that before.

So we arrived in Makemo on 20th January and liked it immediately.

I have long dreamed of getting lost in the Tuamotus for a few weeks and this was really what I had in mind.

Another atoll, a huge lagoon enclosed by reef and islets (motus).

But this atoll is mainly deserted, all the residents live in the village, so the rest of the lagoon is pretty wild.

Our Go-To Motu

We shot in through the NW pass and eyeballed our way 8 miles to Punaruku, a motu with a beautiful spit of sand and reef to protect us from the prevailing trades.

Our kind of neighbourhood. A short dinghy ride to the nearest bommie, healthy coral, clear water and lots of big fish, great snorkelling, spearfishing, no ciguatera.

No phone signal, no internet. We didn’t see another boat, or human being, for a week. Just us and the four black-tip reef sharks constantly circling the boat, hoping I would have another fish to clean and throw them a few snacks.

We can hear the Pacific waves thundering on to the reef on the ocean side of the motu. On this side, the water is flat and breezy.

Another magic wind-foiling playground. Every day I levitate on my addictive cushion of air. Gliding, meditating, balancing the forces beneath my feet, hands and harness hook. Watching the coral heads beneath as I fly over. One morning I find myself staring at the deck of my board, it looks strange. It’s bone dry. It’s been a while since I left the surface.

After a few days we start to think about the rest of the world, we haven’t seen a soul, not even a plane across our patch of sky.

No contact, no news. We wonder how that Brexit idea might be going, what Trump might be up to, that world seems far away. There may have been a zombie apocalypse.

Things got weird one night when we watched a red moon rise over our motu. No light pollution here. The dark moon was rendered like a planet in a 3D sci-fi film. A total lunar eclipse.

The Curious Grouper

I am spending lots of time in the water, stalking, diving and shooting fish. It’s still hit and miss, but I am tuning in to the different fish on these reefs, spotting the camouflaged targets sitting quietly under a coral ledge, recognising the way a grouper swims across the sandy seabed between coral heads. Or the big bump-head parrotfish, so distracted by the bit of reef he is chewing that there’s a chance to approach from above without him noticing.

There are several types of grouper here, my favourite is also called a ‘coral trout’ I think. It seems to be able to change colour, at depth it appears to have a stripy camouflage,

and at the surface is a beautiful red colour with blue spots.

Then there is the Marbled Grouper, looking similar to the Nassau Grouper we were shooting with a pole spear in the Bahamas a few years ago.

They share an unfortunate (for them) behaviour, which makes them the species most likely to be in my frying pan tonight.

When I first arrive at a new fishing spot, a likely looking patch of reef, I anchor the dinghy and snorkel round the area, checking for targets and sharkiness.

Almost all of the Makemo atoll is uninhabited and we are living in some rarely-visited spots. It seems these fish may not have seen a diver with a speargun before, and when I first spot one of my favourite groupers, he will often be watching me very intently. Sometimes emerging from a coral cave to get a better look, or even pausing in open water to hang stationary and let his curiosity get the better of him. I dive down to the seabed close to him, but never looking at him or swimming directly towards him. Having reached the bottom I’ll hold on to a rock and slowly turn to where I think he was, and almost always, he still is!

Fascinated by me and not afraid, or perhaps he is defending his territory. He does not recognise the threat of a double band spear gun when he sees one. Now we have full eye contact, he will continue to gulp and stare, inches from my spear tip, his pectoral fins working alternately as I disengage the safety catch with my thumb and plan tonight’s recipe.

That exact scenario has played out many times and provided many delicious dinners.

The next stage is a rapid ascent, then a brisk swim to the dinghy with the speared fish held above the surface, sometimes pursued by a shark or two.

Compared with catching a fish by trolling a lure from the surface, this seems so much more intimate.

It’s also more efficient. I can select the species of fish I want to eat, and the portion size.

But I have to find him, get down (literally) to his level, out of my comfortable surface environment, picking the moment, waiting outside the grouper’s cave, predicting his behaviour and holding my breath. It seems the grouper has pretty good odds, and he would have, but for that moment of curiosity.

Anchoring in coral.

(Room to swing a cat?)

Dropping a hook in the Tuamotus can be a bit more complex than our usual technique.

Ideally we nose our way in to shallow water, lower the anchor 2 or 3 metres to the bottom and watch it disappear into white sand as I gently pull it back with both engines to bury it. We attach our snubbing bridle, swing on a 15 or 20m scope and don’t give it another thought unless a real hoolie blows up.

Not here. The water tends to be too deep or too shallow. The lagoon bottom comes up steeply from 20 or 30 metres to a reef or beach, so we are looking for the occasional spot where a shelf of sand offers us a likely place to put the hook and enough room to swing a full circle. Even the most reliable looking trade winds here can suddenly die or reverse, so that patch of shallow reef way upwind is suddenly just under our rudders.

It’s so hard to gauge those distances accurately from the deck. So now I swim each time to check it, counting strokes from transoms to anchor, then swimming the same number of strokes from anchor towards any surrounding hazards, checking we have the radius we need.

Another of Moitessier’s old tips. Simple and effective.

The next problem is the coral rocks, boulders and pinnacles. Most of these sandy patches are dotted with old coral growth, of all shapes and sizes. As a boat swings to her anchor the chain inevitably becomes wound around numerous rock structures, which can be tricky to untangle, sometimes involving one of us in the water directing the other at the helm as we drive the boat around, unhooking each loop of this cat’s cradle. Not easy if it’s blowing.

It’s also dangerous if the chain you think you are riding to is actually stuck on the rocks, leaving you with a much shorter scope than planned. Wind or swell can create shock-loads on that length of chain. (See Easter Island post for details).

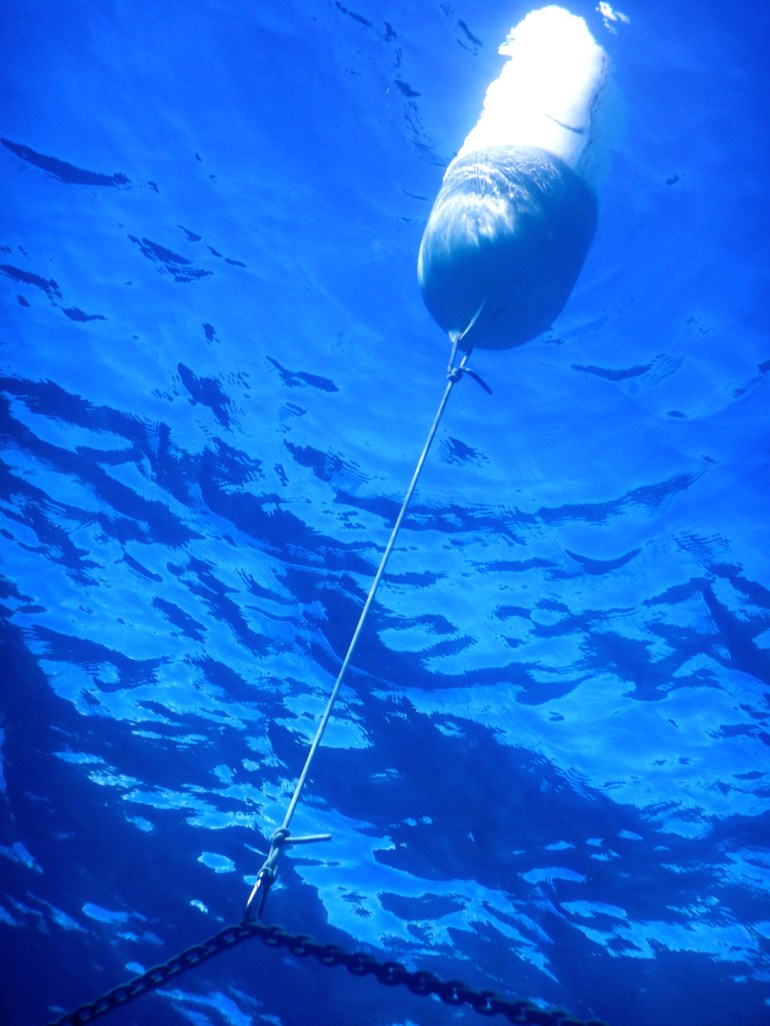

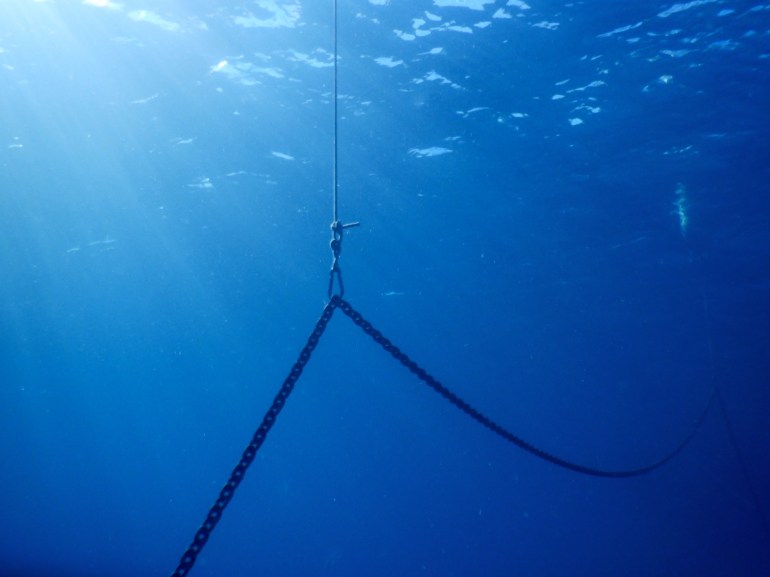

So our new technique is to float the chain. We float two of our big fenders along the chain, clipped on to it with snap shackles on deck as the chain pays out.

The first at say 15m then another at 25m with a total scope of 40m, in 8m depth. It can work really well, with the chain suspended above all the potential snagging rocks. It if blows hard the boat will pull back, straightening the chain and temporarily sinking the fenders.

Another recent addition was a third fender attached to the crown of an anchor with a long (depth of water) line.

If (when) the tip of the hook lodges itself under a rock, we can pull it out from that end, whereas pulling on the chain would only dig it in harder.

I think our anchor is 25 kg. It’s hard to pick it up on deck, and almost impossible to move if I dive 10m down to it. But swimming at the surface, I can use my buoyancy and the anchor’s reduced apparent weight in the water to great effect, pulling up on the line and moving it from a rocky patch to a nice bit of white sand.

It’s a good trick, but every time we put another line in the water, I worry about an unforeseen side effect. It’s another rope to tangle, or wrap around a prop.

This was a good one. A black cloud approached and the wind died, the boat sat on top of her buoyed loops of chain and tangled them in the snubbing bridle. The bridle somehow rode over the fender buoying the anchor line. Then the rainstorm started with wind from the opposite direction, the boat pulled back to the new breeze and the bridle pulled on the line attached to the crown of the anchor. Pulled it out of the sand! It seems so unlikely, but if it can happen it probably will, so we won’t be attaching that line again.

Cyclone Season

We’re not even supposed to be here. This archipelago is technically at risk of a cyclone, though they are rare this far east.

The plan was to be in the Marquesas by now, closer to the equator and a safer bet for this season, which lasts until April.

We are still trying to get there, but the wind’s blowing the wrong way.

More guests!

We don’t generally have many visitors. All those long seasons of lotus eating and navel gazing in the Caribbean, the guest cabin was hardly used.

This year we’re fully booked!

Our next rendezvous is in Marquesas with Cyril and Kirstin, friends from London who are coming to sail with us. But we’re not there.

There’s an airstrip on Makemo, so we re-arrange to meet them here. I think they’ll like it.

It’s all very lovely and inspirational…… but I still worry about all those sharks!! xx

LikeLike

Hi Guys

Inspiring to say the least. Was Georgie there? I would love to see an image of her beauty. She was there right? I jest and would still love to see her.

My daughter, Emily has been with us for a few weeks, super fun for all. Our best to Gemmima (sp?) if you are in touch.

We had coffee with Kathy and Richard this morning. Lovely folk. Our paths will cross again.

As again will ours. Love you two.

Josh and Suzee

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike